Lectio Divina

When I hike, I practice a form of Lectio Divina – allowing me to meditate on the natural elements and the physical experience of the hike. Lectio Divina originated in the third century with the desert elders of Christianity. The desert elders left their worldly lives to become hermits devoted to a life of asceticism, contemplation, and prayer. Even though they thought they left the world behind, they discovered that even in the quiet of the desert they could still be overwhelmed by their negative thoughts. So, they developed a practice of targeting a prayer to destroy negative thoughts right at the moment the thought arises – before it is able to take hold in their minds. They discovered that, by using these little prayers, they could re-direct their thoughts to create space for thoughts of God to spring forth.[1]

Monasteries were organized out of the experiences of the desert elders. One of the foundations of the Benedictine community is the timelessness of scripture.[2] Lectio Divina is a prayerful, reflective reading of scripture. It is so important to the contemplative life that the Rule of St. Benedict makes it part of the daily work schedule. Specifically, a monk’s daily work schedule is a balance of work, Lectio Divina, and prayer.[3]

There is a process with Lectio Divina, but it is important to understand that it is an gentle process. You are not trying to find the truth of the scripture. Instead, you are using scripture to focus your thoughts and your emotions to create space so that God can find you. The goal is to merely stand in the presence of God and let God do the rest.[4]

Today, Lectio is practiced in different ways. The traditional way is to read a short scripture passage slowly, find a word that speaks to you, meditate on that word and let it touch your heart. The goal is to rest in silence so that God can take us beyond ourselves.[5] The process of Lectio can be used with specific prayers (like the Our Father), visual illustrations of scripture, and elements of the natural world. I can always find an element of nature that speaks to me. Lectio Divina engages my imagination so when I hike, my encounter with nature helps me contemplate the presence of God in my life.

Roncesvalles to Zubiri – Lectio with Nature

When I hike, what usually calls to me is the wind. I think it’s because I usually hike in the desert – there are not a lot of trees. Contemplating God as the wind, I have experienced the creative force of God. “[T]he earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters” (Gen. 1:2).[6] Once, on a particularly warm and dusty day, I imagined being in the story of Exodus. I saw myself wandering in the desert having to believe in a God who does not always answer our prayers in the way we expect (Exod. 16:2-12). As I started my walk from Roncesvalles, I expected that I would spend my day meditating on the wind.

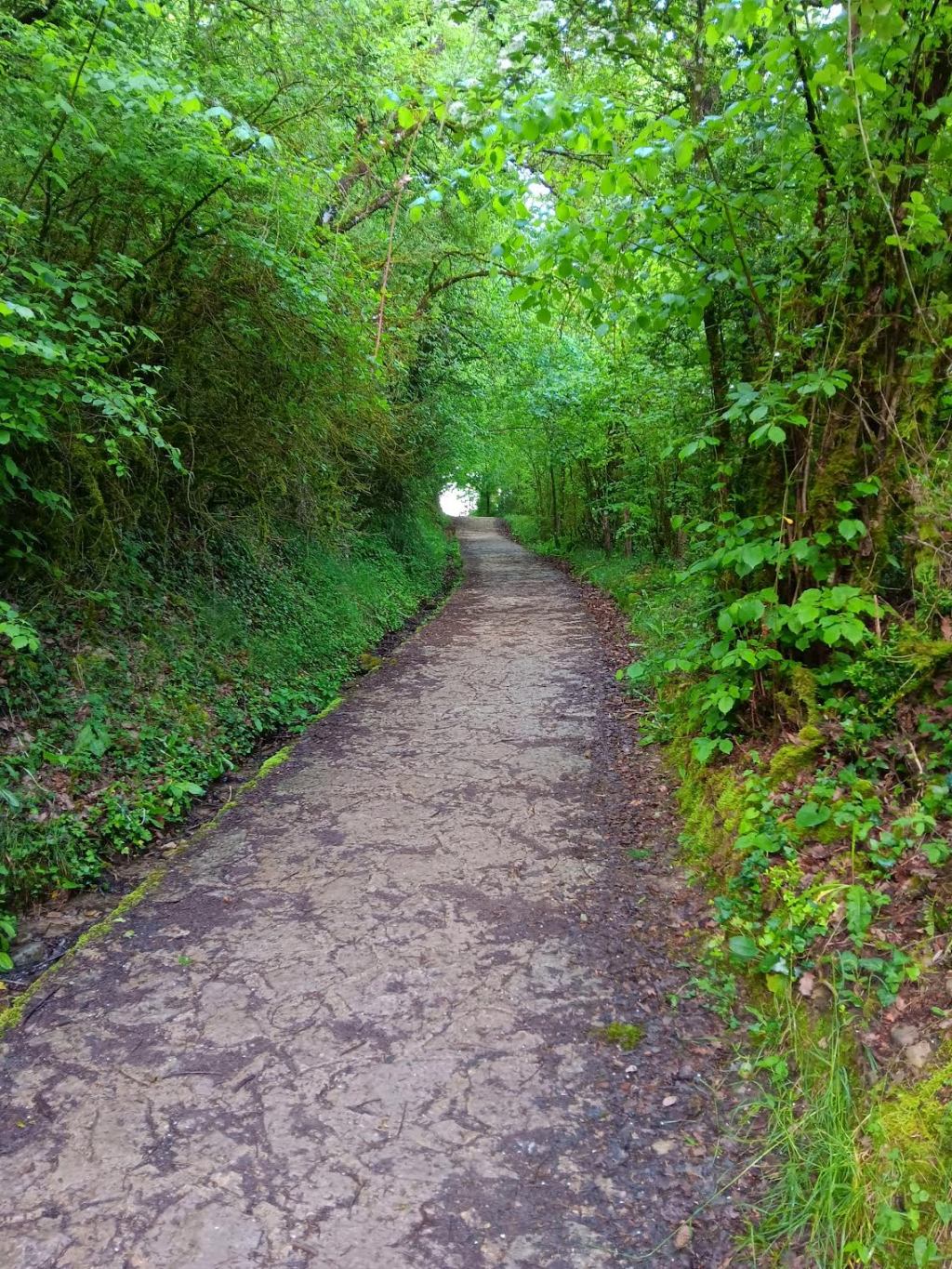

God always surprises me. Roncesvalles to Zubiri is a forest walk. There was no wind. Instead, I was amazed by the color green. The trees felt strong and life-giving. They were deeply rooted in the ground and nourished by the rain. They provided habitat for the animals of the forest. “By the streams the birds of the air have their habitation; they sing among the branches” (Psalm 104:12). As I walked, I felt my connection to the Earth. I asked, “How does this feeling of strength and rootedness of the Earth reflect my experience of God?”

When I think of experiencing God with the strength and rootedness of the Earth, I think of the presence of God within the Benedictine community. The Rule of St. Benedict teaches a way of life where we experience God in the everyday workings of community, and the relationships we share. I learn through the Rule to welcome all, regardless of their financial or professional status, and to treat each person according to their need. The Rule also teaches me humility, making it possible to find God through my willingness to ask for and receive help from others.[7] Joan Chittister, in her book The Monastery of the Heart, explains that Benedictine spirituality has “God at its center and people in its heart.”[8] Esther de Waal describes the Rule as calling us home, calling to our desire to be in the place where we belong.[9] I am not certain it is an actual place we are called to. I think it is this feeling of being rooted – this feeling of God as the Earth.

At my first stop for coffee (before I had to climb the big hill), I spoke with a man who, when he was young, wanted to live his life as a “free spirit,” without being burdened by family obligations. Instead, when he was 25, he had a son. He had to give up his “free spirit” life to support and nurture his son. I could tell that he chose to be the Earth for his son. And today, the family he created with his son is his stability.

After this conversation, I thought of my own experience of being the Earth for my mother. As she got older, she looked to me for companionship and to make certain she was cared for. I chose to be her support and over the years I benefited by having the relationship with my mother that we were not able to have when I was a child. When my mother died, my sister chose to include me in her family – to be the Earth for me. I see God in all of the choices we make to create relationship with others.

Benedictine spirituality is rooted in our humanity, and the humanity of others. It allows us to acknowledge our limits, the differences we experience in our relationships with other people, and our expectations for mutual support.[10] To experience God at the center of those relationships is to develop a relationship with God that is grounded and feels like home. It is God being the Earth for us.

[1] Mary Margaret Funk, Tools Matter (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2013) 1-6.

[2] Joan Chittister, The Monastery of the Heart: Benedictine Spirituality for Contemporary Seekers (Goldens Bridge, NY: BlueBridge, 2020) 21.

[3] Timothy Fry, O.S.B., ed., RB 1980: The Rule of St. Benedict in Latin and English with notes (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1981) Chapter 48. Esther de Waal, A Life-Giving Way: A Commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1995) 158.

[4] de Waal, A Life-Giving Way, 158-159.

[5] de Waal, A Life-Giving Way, 159.

[6] New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

[7] de Waal, A Life-Giving Way, 172.

[8] Chittister, The Monastery of the Heart, 81.

[9] de Waal, A Life-Giving Way, 7, 237.

[10] Chittister, The Monastery of the Heart, 78.

Leave a comment